Purchasing links (the set will be released in the U.S. on February 10, 2015):

Allegro Media Group – CD Universe – Crotchet Classic Value

Discovery Records – Amazon UK

Townsend Records – Base.com – SimplyClassicalCDs

For track listing and details about the recordings, click here.

John H. Haley is the Editor of the Sound Recording Reviews section of the ARSC Journal [Association for Recorded Sound Collections] as of Fall 2012. He is an ARSC member of many years who does audio restoration work with a lifelong interest in both digital and acoustic audio interfaces. He studied classical and popular music, and is a retired attorney. He has a Bachelors of Music degree from the University of North Texas with concentration in voice and piano, and while in college served as a professional chorister for the Dallas Civic Opera. Since 1987 he has served as a Board Member of the Bel Canto Institute (www.belcantoinst.org), an organization that teaches bel canto opera style to young singers every July in Florence, Italy, and is President of the Board since 2005. Ongoing restoration projects include live recordings of singer Yma Sumac sold on www.yma-sumac.com, and live recordings by the violinist Henri Temianka and his quartet, the Paganini Quartet. In addition to the set discussed in the interview, recently published projects include contributions to Johanna Martzy, Volume 3, released by DOREMI, and several tracks for JSP’s Judy Garland: The Garland Variations, both in late 2014.

What was the genesis of SWAN SONGS, FIRST FLIGHTS?

Music critic and theater professor/expert James Fisher had a bootleg copy, in poor sound, of the June 1968 live concert that Garland gave at the Garden State Arts Center in New Jersey. As a teenager he had attended that concert, about which he later wrote for the ARSC Journal, and I told him to send it to me to see if I could make it any more listenable. It turned out that music journalist and Garland expert Lawrence Schulman, whom I also knew through ARSC, had a copy from the same source, with the same poor sound, and I fooled around with this item with my restoration software to see if this material could be made presentable for a general audience. It could not, although I achieved some improvement. Larry, who has produced a substantial number of excellent Garland CD collections, had previously spent several years negotiating the release of the two extraordinary Decca “test” records that in 1960 had been found by Dorothy Kapano on a garbage heap out in front of Garland’s Los Angeles home after it was sold. You can find discussion of these records on The Judy Room website at www.thejudyroom.com/decca/lostdecca.html .

After hearing the work I did on the New Jersey concert, Larry asked me to take a crack at doing new restorations of the two Decca tests. We liked the results so much–you can hear them in SSFF–that we talked about batches of other live material, as well as more of Garland’s earliest recordings. None of the live material had ever been restored well, and the idea evolved of presenting a new perspective on Garland’s artistry by juxtaposing her earliest and last recordings, using modern state-of-the-art restoration techniques to reveal for the first time just how fine Garland’s performances really were at the extremities of her career. Her career is otherwise very well documented, being well known from movies and commercial recordings, but not its beginnings and endings. The main reason for these gaps is obviously the absence of good sounding restorations of surviving recordings. Fortunately, the Canadian record company DOREMI was interested in producing and releasing a set of this material on the new HALLOW label.

How did the title SWAN SONGS, FIRST FLIGHTS come about?

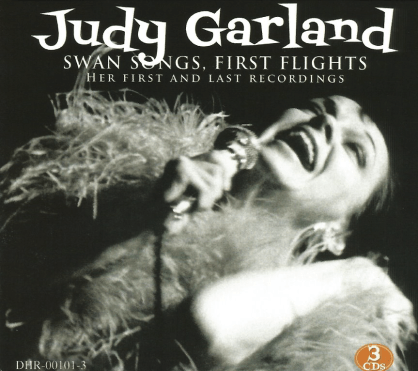

Since it was proposed to include in the set a lot of wonderful but unfamiliar live material from Garland’s last year–she was only 47 when she died—Alain Falasse suggested the title “Swan Songs.” This expression comes from an ancient belief that swans sing a beautiful song in the moment just before they die, and it is used to describe a burst of great artistic activity shortly before an artist dies or retires. Larry then cleverly suggested the complementary phrase “First Flights” to describe the batch of Garland’s rare recordings from her youth. The imagery of an exotic bird was further enhanced by the fact that Garland was fond of feathery stage apparel in some of her last concerts, as captured in some wonderful performance photos, one of which appears on the cover of SSFF.

It has taken you well over a year to master the set. Why so long?

There are a number of reasons. First, the scope of the set changed and expanded as I worked on it. For one example, we originally wanted to include the audio portion of some important US television material from Garland’s last year, but after a substantial expenditure of time, the corporate owners of that material wanted ridiculous, astronomical amounts to use it, so sadly that material had to be scotched.

Some of the source material was coming from amateur recordings made on who-knows-what equipment, and most of it needed a lot of time-intensive work to get things right. For some of this material, achieving great sonic results was out of the question, and in those cases I had to experiment with various approaches to see what would work best, not knowing what the best possible final result could be. These ended up as bonus tracks. Some of the material went through 20 or 30 versions before a satisfactory result was reached. The mountain of rejected computer audio files that I have accumulated reminds me of the lab scene of failed Lt. Ripley clones in the movie Alien Resurrection. We also found that some factual and legal investigation and research was needed or helpful, and that also took time.

What were the specific problems you ran into during the restorations?

Correct pitch is probably the most crucial factor in restoring live material, as very small changes in pitch can drastically change the sound of a human singing voice, as well as the emotional feel of a piece of music. Except for the excellent Copenhagen source tapes, almost nothing was on pitch. For some of the concerts we had to rely on multiple sources, and none of those were at the same pitch. Some items had apparently been pitched by someone previously, but not always correctly. For some items, the pitch was inconsistent, shifting over time during the course of a song, as the original recording was not made on professional equipment or even sophisticated consumer equipment. The early records likewise had to be pitched correctly, as records from that era are anything but standard in their playing speed, and instantaneous recordings and transcription discs must always be carefully pitched. All of this had to be fixed.

Photo from the collection of Kim Lundgreen.

Apart from getting things on pitch, there is the related issue of determining the correct keys. There is no book where you can look up the key in which Judy Garland sang a particular song on a particular occasion. In some cases it comes down to a judgment call as to what the correct key is, and choices must be made based upon all the available clues. Ultimately, it is the sound of a voice that is the most important factor. Larry and I spent a good deal of time dealing with these issues, and we are confident that our deliberations succeeded in arriving at the correct keys.

Noise removal was of course another very big item. Some of the material was recorded in the midst of really large and/or boisterous audiences, resulting in enormous amounts of audience noise to contend with, the best example being the huge audience at the Philadelphia stadium concert, but also the drinking crowd at Talk of the Town, a London nightclub. Further, the fact that some sources had been copied from tape to tape, prior to the digital era, probably more than once, meant that many items contained generous amounts of tape hiss and broad-spectrum noise. Some items included massive natural reverb, as microphone placement is not a matter of choice where something is taped from the audience at a live event, and some had obviously been “juiced” with fake reverb. How much noise or reverb to remove, by what method, and the point at which that process starts to cause audible losses to the music are issues that result in an endless series of judgment calls, and frankly, a lot of trial and error.

Some of the hardest and most time-consuming items were the ones that sounded the worst–items that cannot be made to sound better than fair. While in general the goal was to give people things that sound good enough that the splendid live performances can be enjoyed without reservation, there were some items that were so important that they called out to be included despite their more marginal sound quality.

For example, research indicates a very strong likelihood that the three songs Garland performed at the London Palladium in January 1969, simply do not exist in any better recording than the dull sounding source that was available. With these items, the fact is that we must consider ourselves lucky to have them at all. A huge amount of restoration effort was required to achieve a result that is still far from ideal given the absence of upper frequencies, but Garland’s spirited performances nevertheless come through, justifying inclusion of these very rare items.

Similarly, while a better source for the Harold Arlen songs at the November 1968 Lincoln Center concert ought to exist, it has never surfaced, and at this point it appears that the compromised, audience-taped source is probably all there is. In retrospect, it seems unbelievable that no professional recording was made of that hugely momentous concert for commercial release, being a tribute to legendary song composers Harold Arlen, Vincent Youmans and Noel Coward. Even in the poor source we can hear that Garland’s performances on that evening were nothing short of fabulous, maybe even the performing highpoint of her last year, but oh that source, riddled with hundreds of large and small tape dropouts! Thankfully a good amount of restoration was possible here, though it was arduous and very time-consuming, with all the many drop-outs having to be repaired individually, one by one. I also used a new reverb reduction feature of the newest restoration software to reduce some of the heavy echo from the sound, caused by poor mike placement. While the result is still not great sound, it is substantially improved, and we are fortunate to be able to enjoy Garland’s vibrant contribution to this important live occasion, only seven months before she died, in a much better way.

You are president of the board of the Bel Canto Institute. Is there a connection between bel canto and Judy Garland?

I have been a board member of Bel Canto Institute since it was founded in 1989 by my friend of many years, Jane Klaviter, who just retired from the Met Opera, where she was assistant conductor, prompter and coach for many years. The purpose of Bel Canto Institute is to teach both bel canto opera style and Italian language to young opera singers for four weeks every summer, with the program now being held in Florence, Italy [see http://www.belcantoinst.org/].

There is an indirect connection with Judy Garland, who of course was not an operatically trained singer though certainly a very well trained one. Singing voices are ultimately singing voices, however they are used, and many of the principles of excellent singing apply across the board. The very most important element of good bel canto style is the ability to sing legato, the way of connecting notes in a smooth line to create expressive musical phrases that can carry potent emotional content. This learned skill can only be accomplished with solid breath support, that is, keeping the tone coming out steadily by maintaining an even, unforced emission of air across the vocal cords, letting them vibrate freely without strain or undue muscular effort. Breathing is controlled by the diaphragm, a large abdominal muscle, but the essence of great singing is careful coordination rather than heavy muscular effort, among all the involved body parts used to create sustained tones.

Garland had a very well developed sense of solid breath support, no doubt stemming from the time of her having to project her singing voice on stage to vaudeville audiences since the age of two and a half. Beyond possessing a voice of great natural warmth, she had the ability to achieve stunning musical effects with legato phrasing, buoyed on her breath, in much the same way that a great opera singer does, and unlike a great many pop singers who never develop this kind of singing skill.

There is another connection between Garland and opera to be noted, and that is the sense of active drama created by her, “on the spot,” in live recordings. This aspect is especially apparent in her later live recordings, where the more placid beauty achieved in the studio version of a song has been cast to the winds, replaced by an “all stops out” portrayal of a specific human being who is actually experiencing the emotion inherent in the song, which has now taken on its own on-stage pocket drama. In this sense, Garland’s performances became “operatic” in non-operatic material.

You are also sound recording reviews editor for the ARSC Journal [Association for Recorded Sound Collections], which has published a great deal on Garland over the past two decades. Did your connection to ARSC spark your interest in Garland?

Yes, in the sense that I was an avid reader of the ARSC Journal for many years before taking on the editorship of the sound recording reviews, the focus of which is historical recordings. I always enjoyed reading about Garland, whose performing I already admired. I think the same must be true for everyone who has ever experienced her remarkable performance in The Wizard of Oz. How could you not love Judy Garland after seeing and hearing that one movie?

You are also a lawyer. Was this a plus in working on the set?

Yes indeed. Sometimes I wonder how anyone can get through the week without being one. In the last year I have retired from law practice completely to focus on other things I want to do. My undergraduate degree is in music, which has always been an avocation, and for many years I have endeavored to understand the implications of copyright law as it relates to recordings, which can be a quite murky area in this country, and one that is widely misunderstood. I have also learned about Canadian copyright law, since the SSFF set is being produced in Canada, as well as EU copyright law because so many historical recordings originate from Europe. This legal knowledge has now become useful to my audio restoration activities, in a general way.

Also, it is an understatement to say that Garland did not lead a tidy life from a legal viewpoint, and I found myself wondering about the legal implications and consequences of certain aspects of her life and performing career. These thoughts were highlighted by the difficulties that some prior Garland projects reportedly encountered. My investigation confirmed to me the propriety of the SSFF set and the absence of legal impediments. At some point perhaps I will write an article about all this.

Tell us a little about the label, DOREMI. Isn’t it basically a classical label?

SSFF is the first release on a new DOREMI imprint, HALLOW. DOREMI is one of the leading historical classical labels in the world, with a large catalog and worldwide distribution. Its founder Jacob Harnoy is one of the very best and most experienced audio engineers there is. Before founding DOREMI, Jacob had a career as an academic and research scientist in physics and nuclear engineering, but he was originally trained as a classical violinist. His lifelong focus has been music, and he has a sensitive musician’s ear as well as superb musical taste. As a company, DOREMI has occasionally branched out into various non-classical areas, and it has always possessed an adventurous spirit, with a healthy focus on the release of live material, preserving precious live sound documents for future generations that would otherwise almost certainly get lost. DOREMI has also consistently been driven by a belief in artistic quality as the primary criterion for inclusion of a particular artist or recording in its catalog.

Judy Garland is an excellent fit with this label because she herself was a serious concert artist in her own musical genre—what is now referred to as the “American Songbook”—and the passing of time has only increased her reputation as an American “classic”—quite the opposite of many popular artists who, whatever their intentions, personify the concept of ephemera. Today’s listeners have no problem taking Garland just as seriously as an artist as they do classical musicians, and the quality of her artistry continues to fascinate and move listeners through the medium of recording. Though she herself would probably have laughed at the idea, she has also become “historical” in the half century that has gone by since her premature death. She may seem perfectly contemporary and present before us in her live recordings, but in fact she belongs to a very different era.

Do you have a personal philosophy regarding audio restoration?

Yes. I have to agree with my friend Jon Samuels, an audio restoration guru for many years, that the first rule of audio restoration is the same Hippocratic oath that doctors take: “Do no harm.” It’s really all about the music, not about the egos of the people who step in between the performing artist and his or her ultimate audience. The goal for a restoration person is to be invisible. If I have done a good job on something, a listener should be unaware of my work.

From the collection of Lawrence Schulman

In that you have spent hundreds of hours listening to Judy Garland’s voice, how personally would you describe it?

I fundamentally disagree with the descriptions you will see of Garland’s voice as a contralto. I just do not hear that. Contraltos are quite rare in the general population, at least those with useful singing voices, and the various “earmarks” of such rare voices are not heard in Garland’s voice. Rather her vocal quality was that of a soprano, though not a high, light one. From her earliest years she had adapted to sing comfortably in lower keys, with her “high notes” set up to fall within the upper part of her powerful “belt voice” notes lying in the area of about a half-octave below first-line C (the C above Middle C on the piano). The operatic soprano’s High C lies an octave above that. Apparently she avoided developing her normal soprano upper register very much.

She “came of age” vocally in the era of radio and the microphone, which drastically changed the ways in which many performers sang when compared to the prior “acoustic” era, when performers had to rely on their own innate vocal projection to make their singing voices heard in a hall or theater, without electronic amplification. However, her childhood as a vaudeville performer belonged more to that earlier era, laying the groundwork for her later vocal development. The microphones and radio broadcast equipment that she encountered as she matured did not much like the extra intensity belonging to the normal upper ranges of both male and female voices, with the result that pop voices became cozy, smooth and most of all, low.

Garland’s natural voice was a quite beautiful one by any standard, and it was unusual in that it quickly returned to a solid, healthy “middle voice” placement once out of “belt register,” with these register transitions magically appearing seamless. The way her voice was structured will not work very successfully for most female voices, especially over the long term, and countless female voices have no doubt been wrecked trying to imitate Garland’s particular sound. In her case, the innate beauty of her easily produced middle voice never deserted her, as can easily be heard in SSFF. Also, despite singing in low keys, Garland generally avoided forays into braying operatic-style chest tones, which are often “part of the equipment” for heavier sopranos, as such tones were inconsistent with her interpretive goals. Her transition into the bottom register was both gentle and kept low, taking advantage of the natural fullness of her middle voice.

From a technical standpoint, the way Garland sang was no doubt facilitated, and her vocal longevity maintained, by a very well developed and disciplined approach to breath support instilled in her when she was young, that fortunately for her became habitual. She generally sang right “on the breath,” as singers say, with singing and speaking coming easily from exactly the same place, a desirable quality in every singing voice. This breath support served her very well in her forties, when there were inevitable changes in her maturing voice, allowing her to maintain a high vocal performing standard even when her overall health was not the best. Her debilitating lifestyle issues—sleeplessness, poor eating habits, reliance on pills—seemed to have little effect on her vocal mechanism, thanks largely to this underlying strong sense of breath support, although we are sometimes aware of diminished stamina, requiring some crafty husbanding of vocal resources on her part. Yet, overwhelmingly, she succeeded.

What you will hear on SSFF proves beyond any doubt that Garland’s voice was intact at this point in her life, remaining fundamentally steady and more importantly, readily able to do her bidding interpretively without any ruinous sense of compromise. This is just not how damaged, worn voices sound—all wobbly and hoarse with rough register breaks, begging the audience’s indulgence. None of these flaws were in Garland’s performing vocabulary.

This is not to deny that Garland’s voice was changing from what she had sounded like in her 20’s or 30’s. Changes in singing voices with age are perfectly natural, and where singing skills are well developed there are often plusses as well as minuses. While there will of course be a variety of opinions on this subject, I for one like a number of things about Garland’s mid-40’s voice, even though it is admittedly not entirely the same voice listeners are accustomed to from her most familiar periods of commercial recordings years earlier. As heard in SSFF, it is definitely lighter in texture than in previous years, with perhaps heavy pressing on the tone for size no longer being within her grasp, but the flipside of this issue is that overall, the resulting tone has an appealing lightness, perfect crispness, and at its best, a palpable sense of buoyancy—with perhaps less of a sense that the act of singing is heavily taxing her vocal resources, at least as compared to how she sounded in her 30’s. She does tire vocally a little quicker, with the length of breath being a little shorter, but the musical flexibility and great adaptability of her performing skills generally take these issues in stride, negating them as serious impediments. Things can still go wrong, but the listener must remember that these are live performances where things can always go wrong, for any performer. What is important and what cannot fail to impress is the totality of all the things that go so right.

Then there is the issue of tuning. While Garland always had a pretty clear sense of pitch, in her “middle” years, even in commercial recordings but especially in preserved live appearances such as her TV show, the pressure placed on the tone, perhaps stemming from her belief that a “trooper” must deliver the goods even when vocally tired, resulted in too many tones being a little off-pitch. Of course the stunning quality of the performances as a whole generally carried the day. However, by her mid-forties, as heard in SSFF, there has been a tangible improvement, with staying right in tune being apparently easier for her. Any voice falls more easily on the ears when it is well in tune.

Despite the discussed changes, the evidence provided by SSFF affirms that Garland’s voice, performing persona and interpretive spark were still all “of a piece” throughout her long performing career, starting when she was a little girl. I am hardly the first to comment that Garland’s voice was unique. I have heard a great many singing voices of all kinds over the years but I have never heard another one remotely like it—none of her recordings could possibly be by anyone else.

You clearly had the cooperation of John Meyer for SWAN SONGS, FIRST FLIGHTS. Could you describe John for us?

John is first of all a very gifted pianist, but also an excellent song composer. He is a multi-talented fellow all right, as I really enjoyed reading his published account of his relationship with Garland, Heartbreaker, which was very well done. As a pianist, he plays very fluently by ear, a skill I lack as a pianist, and I am very jealous of his ability to provide just the right accompanying musical bits, that seem to flow out of him very easily on the spot, to capture the right mood of any song.

We were fortunate to be able to include in SSFF pieces of his tape of his rehearsal with Garland made in the living room of a New York apartment, capturing Garland’s voice in what is most likely the only recording we have of her mature voice projecting a song into a room without amplification. This is in fact what she really, truly, unquestionably sounded like, unvarnished and unimproved. And what that is, is fresh and wonderful. The recording is not perfect, as the mike was obviously closer to the piano than to Garland, meaning that we pick up her sound more from the perspective of somewhere out in the room than up close, sometimes competing with the piano tone. But you know what? It’s still wonderful. What I did here is edit the tape into two actual song performances, eliminating the starting and stopping and the normal verbal discussion that occurs at such a rehearsal. The complete tape appears as a CD included with Heartbreaker.

Otherwise, in SSFF we get to hear Garland perform contrasting versions of one of John’s great songs, for which he also wrote the lyrics, “I’d Like to Hate Myself in the Morning.” Garland clearly liked this song a lot, as she programmed it very frequently after first performing it on The Merv Griffin Show in December 1968. The song featured prominently in her month-long act at Talk of the Town nightclub in London in early 1969, and a special treat appears in the SSFF bonus tracks for Talk of the Town, where Garland performed it after inviting John up on the stage with her, while he injected commentary as she sang. Sadly, plans to include another great song of John’s, “It’s All For You,” which Garland sang on the Johnny Carson show in late 1968, had to be scrapped after that show’s corporate owners demanded an insane amount for its use.

Did your appreciation of Garland change after such an intensive period of work on her recordings?

Yes. Like almost everyone else, I was previously unfamiliar with Garland’s work after her last period of commercial recording activity ceased several years before the 1967-69 period covered by the set. I was very pleasantly surprised to discover the high quality of her late work, after approaching the prospect, I must say, with lowered expectations based upon the false notion that she had “lost it” by that point. Only after I restored the late concerts included in SSFF and heard them for what they really were, did I come to appreciate Garland’s enduring resilience and phenomenal strength of spirit. After taking so many hits to her life and career—the kind that could be expected to finish off most performers, Garland could walk out in front of a live audience, knowing exactly who she was, and deliver a show that was still near the top of her game as a performer—a star undimmed by mid-life’s disappointments and vicissitudes. Life may have dumped all over her, but when it came down to the basics of something she really cared about—giving an audience a thrilling program—she just didn’t seem to care about “the small stuff.” I think there are some lessons for all of us in that.

Did the early recordings – or FIRST FLIGHTS – present different challenges for you?

Yes. They come from a quite different era of recording, the 1920s, 1930’s and 1940’s, and can only sound like it. Some issues were similar to those presented in the later live recordings—primarily getting them on pitch and reducing noise, but the whole concept of what such an earlier recording should sound like is different. You have to keep those fundamental differences in mind, and in your ears, to come up with the best sounding thing that you can. To some extent, I was able to reverse some severe compression in some tracks, and many of the older recordings required some EQ to rebalance the sound. Plus there was the overriding issue presented by the earliest tracks, of understanding what children’s voices ought to sound like, and then deciding what these particular children’s voices ought to sound like. That is the worst failure in prior versions you can hear of these items—the children just don’t sound like human beings, even very young ones.

I understand that it took you several months of work on the 1935 Decca tests, which in your restoration sound markedly better than their previous release. Could you tell us about your work on those two recordings?

The digital transfers, which are what I had to work with, of the original rare records were incredibly noisy, indicating that the records had come through a very rough history. The raw versions sounded something like a hail storm landing on a tin roof. Getting the noise out as much as possible, while hurting the vocal and piano recording itself as little as possible, was the big issue. What this boils down to is trying to preserve all the legitimate high frequency musical content that you can, so the voice will be clear, while eliminating or at least minimizing all the competing broad spectrum surface noise that you can. This is not so easy. I used computerized noise removal features up to a point, but they are not very effective in large doses on such a noisy source without damaging the musical sounds, so I had to do intensive manual noise removal throughout each song, removing clicks, pops, clacks and thumps individually. This process is fairly effective but tedious and slow. I also rebalanced the recordings with EQ to achieve what is to me a natural sounding result, especially of Garland’s voice, as opposed to the rather tinny sounding original dub. It is impossible to know what phono-equalization curve was used when these instantaneous records were cut, and you have to rely on your experience and your ear to “get it right.” The result still has a certain amount of surface noise; I experimented with various ways of removing some more of it, but nothing was effective that did not also hurt the good clarity of the voice I had achieved with so much manual work, so I ending up leaving the remaining surface noise. For me, Garland’s vibrant young voice jumps right out of the speakers in a quite tangible way. By the way, the slight reverb you hear on my restoration of the Decca tests in SSFF was not at all added. It is the natural reverb of the room in which Judy was recording. I am quite proud of that accomplishment.

The brochure for the set is rich in texts and photos. Can you tell us who designed it, and just how it was put together?

Larry conceived the basic layout and Andrew Aitken in the U.K. did the design using the photos selected by Larry. The photos relating to the live events included in SSFF came from private and commercial archives. Few quality photos are extant for some of the live shows, Philadelphia in particular, and Larry took on the task of finding them. I wrote booklet text about mostly technical aspects, and Larry supplied his excellent essay providing an overview of the content of the set. Two other Garland experts supplied helpful text supplementing Larry’s essay—Scott Brogan of The Judy Room website discussed discographical matters, and song composer John Meyer described how his rehearsal tape recording had come about. But the real subject of all of these textual pieces is Garland herself. A set with this many individual tracks also required a good amount of work on the track lists, which of course changed over time as the project evolved and developed. Larry did a great job of “riding herd” on all the detailed tracking information.

What was the easiest part of remastering the set? And the hardest?

The easiest part was restoration of the Copenhagen tapes, which were excellent copies, in pristine condition, of the original broadcast tapes made by Danmarks Radio. Some restoration was still required, but the very clear, well balanced sound quality of these tapes was a pleasure to work with. The hardest parts were undoubtedly the Talk of the Town tracks, coming from various sources at a variety of pitches, sometimes inconsistent throughout a single track, and presenting a catalog of restoration problems to fix, including some bad things that had been done previously that required “undoing.” After literally months of work, most of these tracks came out pretty well. The orchestra mostly sounds very good, though playing too loud much of the time, but the inadequate quality of the club’s PA system carrying Garland’s voice is also all too well portrayed in some instances. But this is what the audience was hearing live, and the recording itself is not to blame. The less good sounding tracks, which still contained important content, became bonus tracks after an inordinate amount of work on them.

Restorers have sometimes been said to be playing God vis-à-vis what they decide to do with a specific recording. Do you feel this way?

That is probably for others to say. I sure don’t feel like “God” when faced with making hundreds of small decisions to improve some bad sounding thing. There is generally no one big thing that makes for a successful restoration result, and rather it is the sum of countless small decisions, driven by an overriding persistence to get everything as “right” as it can be. As stated above, the goal is to make myself invisible, while bringing the listener closer to what was going on, on the other side of the recording process, as Garland or someone else performed. This goal is necessarily fraught with imperfections, but you try your best, using all your skills and the computerized tools available to you.

You have extensively written about Yma Sumac? Is there a connection with Judy Garland?

Not really a direct one. Both were iconic performers whose greatest periods of fame overlapped somewhat time-wise. Both were born in 1922, although Sumac’s international fame did not begin until 1950, by which time Garland’s name was already a household word. It is hard to draw comparisons, really. Their vocal repertoire overlapped very little, if at all, and their voices and the methods they employed for thrilling audiences were utterly different.

Any other observations you would like to share about SSFF?

Yes, some unrelated comments. While this was unplanned, I noticed that the final set includes Garland performing with a number of people who played significant roles in her development or career, not counting the various conductors and bandleaders. First, Garland’s mother Ethel Gumm, though a harsh “stage mother” according to the adult Garland, set her on the path to become a performer. Her mother plays the piano on the two Decca Test sides, and these seem to be the only recordings we have of her performing. Garland’s two older sisters are heard with her in the several “Gumm Sisters” tracks and the one “Garland Sisters” track. Undoubtedly her older siblings, with whom she frequently performed, played a big part in her early development. In “I’m Feelin’ Like a Million,” we have her mentor and coach at MGM, Roger Edens, providing the Gershwin-esque piano accompaniment. It is known that he was responsible for the polishing of her talent at MGM when she was a young girl, and perhaps he also played a role in her solid vocal training. In the Lincoln Center tribute we have the great song composer Harold Arlen accompanying her on the piano in his song “Over the Rainbow,” one of his many standards that are strongly identified with Garland to this day. Then we have two men who were romantically linked to her, John Meyer, accompanying her on his rehearsal tape and appearing on stage with her in London, and her final husband Mickey Deans, working on a new song with her, “When Sunny Gets Blue,” from the keyboard, only a few days before her untimely death. I am not aware that we have any other recording of Deans playing the piano. He also appears in the Danish radio interview with her, speaking of course.

Another comment is that the live performances seem to show just how much Garland relied on audience feedback during a show, to carry her along. In the Philadelphia stadium show and the Talk of the Town tracks, we can hear how her lively interchanges with the audience become a big part of the show. Garland establishes a direct connection with the audience, which then generously responds to her. However, in Copenhagen we hear that the reserved Danish audience does not give her much feedback, causing her to work very hard to get a response out of them. I spoke to some Danish people who told me that their countrymen are respectful and simply less demonstrative as an audience, but surely they were enjoying the show as much as any other audience. Perhaps fewer people in the audience could understand Garland’s English commentary? In any event, this concert, as we have it, turns out to be a considerably shorter one than the others, even though Garland was performing memorably. It is unknown if perhaps some songs were eliminated by the radio station that created the tape, for timing reasons.

My last comment is that this set complements another one recently compiled by Larry entitled “Judy Garland: The Garland Variations: Songs She Recorded More than Once.” That set is comprised of commercial recordings of songs that Garland recorded multiple times, so listeners can compare how flexible she was musically in her renditions of various songs. The same exercise is possible with the live material in SSFF, as some of the core songs of her late concerts appear multiple times. It is astonishing how different they can be, yet always successful taken on their own terms. Matters of tempo, key and style of accompaniment can vary considerably from one show to another, with the various conductors obviously having different “takes” on the same musical material even when the orchestra parts being employed are the same. What we learn here is that Garland was a great master of adaptation, responding instantly to almost any musical situation and turning it to her advantage in putting across a song. She was obviously fearless and felt unconstrained. For one good example, listeners should compare all the ways in which she performs one of her signature songs, “Over the Rainbow,” in SSFF. All are heartfelt, but she is quite different each time. For me, the hushed atmosphere of the Copenhagen version strikes me as the most poignant, but others could easily differ in their reactions. In all of them, she has lifted the song up into a much larger context than Dorothy in Kansas.

If today you were in the same room with Garland, what would you say to her?

That’s a tough one. I wish I could play for her the records she made when she was a child, as finally restored to sound more natural, to see if perhaps she could like them better. I think everyone would like to lecture her about her lifestyle issues, taking better charge of her own life and dealing more appropriately with her health issues arising in middle-age, even though such lectures would be extremely presumptuous coming from a stranger, and we know a lot more personal detail in retrospect than was known generally at the time. One would like to give her encouragement somehow, confirming to her how important she was. Even the most gifted people need to hear that. And finally, to thank her for her generosity of spirit, for all that she gave.

© 2014 Scott Brogan, The Judy Room & Judy Garland News & Events

Purchasing links:

Allegro Media Group – Discovery Records – Amazon UK

Townsend Records – Base.com – SimplyClassicalCDs

Get track listing details and more at

The Judy Garland Online Discography’s “Swan Songs, First Flights” page.

where can i order this cd ?

Click on the order links at the top of the interview page.

How cool. The perfect holiday gift…for myself…LOL. I hope everyone is having a healthy and happy holiday season.

Thank you Scott for once again bringing such rarities to our attention. With only 500 copies being produced this is something that cannot be missed and as it is Garland’s recording legacy that I remain so enamoured of a purchase that is non negotiable! 🙂

Has anyone been able to get this CD yet. I have it on order in 2 places from the UK and still can’t get it!!! I want this CD set bad!!!

A couple of people have reported as already receiving their copies. Be patient. Check your order status with the online retailer.

Thanks Scott. I hope I can get my copy soon 🙂

What a fantastic interview! I can’t wait to get this set to hear the improved audio quality.