“Listen to what she does with By Myself, Mean to Me and Gotta Right to Sing the Blues; every phrase is charged with feeling, polished, developed and underlined by the singer’s natural histrionic talent; she sobs, croons and nearly bawls, but what a performance!” – John Masters, 1957 review of the “Alone” album

November 6, 1934: Here are two notices from this day’s issue of “Variety.” Both of the articles rave about Judy and her sisters (The Gumm Sisters) engagement at “the Chinese” (Grauman’s Chinese Theatre) in Los Angeles.

The first article notes how The Gumm Sisters stopped the show. The second is an article solely about the trio singling out Judy (Frances) which has been quoted in several books. Judy gets all the praise. The second article mistakenly gives Judy’s age as 13 when in fact she was 12.

Of note is that the trio was listed as “Gumm.” This was well after their name change to “Garland” that previous summer in Chicago. The sisters did not receive any billing in any of the newspaper ads so it’s unclear if they were billed locally as “Garland” but billed as “Gumm” in “Variety.” In fact, and in spite of the great “Variety” notices, the sisters were not named in any of the articles about the show which were merely short mentions at the end of articles about the new film playing at the Chinese, The Count of Monte Cristo. The show’s headliner, Raymond Paige, and his “California Melodies Orchestra of 40” received all of the press mentions, and were part of “Sid Grauman’s Most Magnificent Prologue Innovation” that preceded the showing of the film. The sisters were part of the normal vaudeville line-up.

November 6, 1935: Judy’s very first portrait sitting for MGM. She was 13-years-old.

November 6, 1936: Here is an article about Stuart Erwin, who was one of the lead stars in Pigskin Parade. Erwin was nominated for Best Supporting Actor for his performance. Judy gets a mention.

November 6, 1937: This snapshot was taken of Judy on the set of Everybody Sing then in production. The day must have been a short one for the cast and crew of the film because this was also the first of three days of work for Judy on the MGM Christmas Trailer, Silent Night. The short was rehearsed, recorded, and filmed from November 6 through 8. Judy most likely had music rehearsals for the song “Silent Night” after working on Everybody Sing.

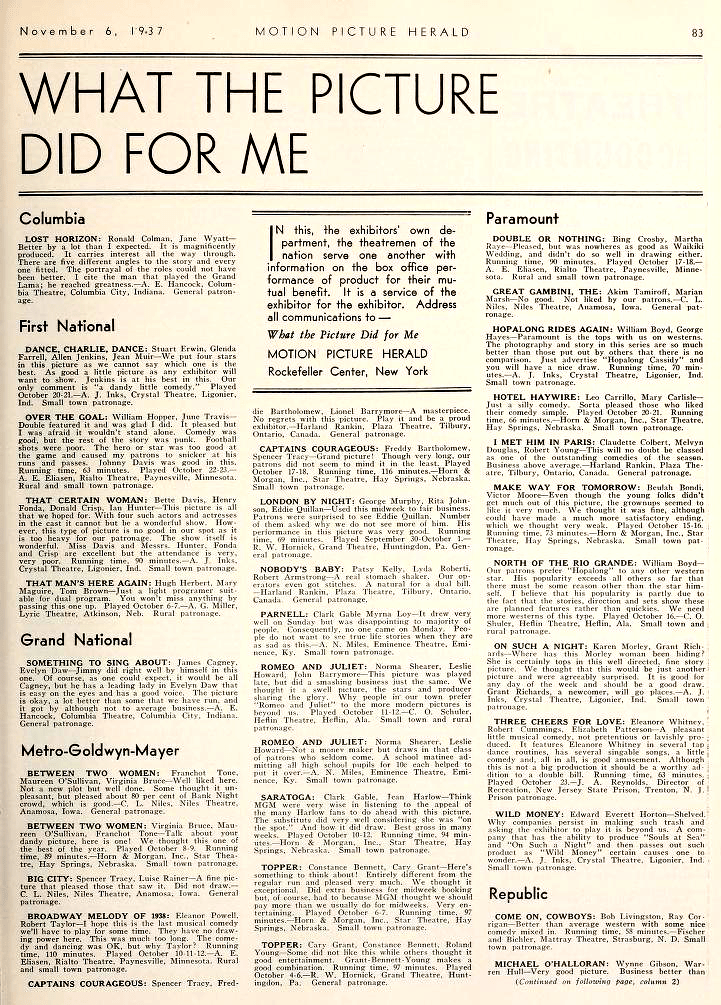

November 6, 1937: Broadway Melody of 1938 was one of the “Motion Picture Herald’s” September Box Office Champions. In the same issue, in the magazine’s regular “What The Picture Did For Me” feature, A.E. Eliasen of the Rialto Theatre of Paynesville, Minnesota, had this to say about the film, “I hope this is the last musical comedy we’ll have to play for some time. They have no drawing power here. This was much too long. The comedy and dancing was OK, but why Taylor?”

November 6, 1938: This rather pedestrian “review” of Listen, Darling was published in the Star Press paper in Muncie, Indiana.

LOVE IN TRAILER IS FILM THEME

‘Listen, Darling,’ Sparkling Comedy At Strand

Love in a trailer is a literal description of “Listen, Darling,” new comedy featuring Freddie Barthomew [sic] and Judy Garland and opening at the Strand Theater today.

The picture is a bow of recognition to thousands who have put their permanent or temporary homes on wheels and made all of America their back yard. Fully half of the action in “Listen, Darling,” takes place in and around two trailers, requiring the building of two of the smallest motion picture sets on record. For those who like lavishness as the background of their romance and comedy, however, there are other elaborate and expensive sets.

“Kidnap” Girl’s Mother

“Listen, Darling,” is the story of two kids who “kidnap” the girl’s mother in the family trailer to prevent her from marrying the town banker and set out upon the highways to find a suitable husband for her.

Mary Astor plays the mother and the “suitors” encountered are Walter Pidgeon and Alan Hale. Gene Lockhart is the unwanted banker and little Scotty Beckett appears as a small but effective menace, who manages to make things mighty uncomfortable for Dan Cupid. Freddie Bartholomew appears in a sympathetic role that is in sharp contrast to the unpleasant characters he has played in many of his pictures. Judy Garland, besides singing three numbers, has an emotional opportunity such as has not been afforded her to date on the screen.

“Listen, Darling,” is based upon Katharine Brush’s magazine story of the same name.

November 6, 1938: Another review of Listen, Darling, this time accompanied by a photo of Judy with her new niece, Judalein.

November 6, 1940: From the papers.

Check out The Judy Room’s Filmography Pages on Little Nellie Kelly here.

November 6, 1940: MGM’s publicity department put out this amusing story about Judy’s college plans. In hindsight, it’s too bad she didn’t actually learn to manage her business affairs as she’s quoted in the article.

Judy Garland Has ‘College’

There’s a new institution opening – the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer College. And for the fall term, its star and only student is red-haired, golden-voiced Judy Garland.

If you knew Judy, the fact that she’s going to school after her 18th birthday would surprise you. Even a year ago, Judy was joyful looking forward to the day when no law could make her go to school.

But the date came early in June and Judy decided that, with only a couple of weeks to go, she should finish her high school course. She did, and graduated, without publicity or photographers, with the class at University High.

Now she’s decided she wants more of the fountain of knowledge. She’s called back her private tutor, Mrs. Rose Carter, and says: “Even though my motion picture work keeps me from going to college, I’m going to try to make college come to me.”

“College” Unrecognized

State laws require private instruction for all juveniles working in pictures. But no one, at least at M-G-M, has ever continued past high school. Judy’s college won’t be recognized by any association of universities, but that isn’t bothering her.

She’s mapped an ambitious program. Music, naturally, will be one of the subjects. Her interest in signing has brought her a music library containing 2,500 records – from Bach to Benny Goodman. She’s studying piano, too.

The curriculum also includes third-year French, art, a second year of English literature and first year economics, law and philosophy. Sounds heavy, you say, for a girl who must spend hours of almost every day on a movie set? Let Judy tell it.

“Law has always interested me, and there’s no reason I shouldn’t know more about it. Law and economics will help me manage my business affairs, or at least know if they are well handled. Someday I want to travel, and I should know at least one foreign language. Literature, art and music will broaden my interests, I believe.”

But how about the college life she’ll miss – the classroom contacts, the sorority house, the proms?

“I’ll Have Advantages”

“Maybe I’ll miss some things,” she says, “but I’ll have advantages no student in a regular college will. Here in the studio I meet people who have been all over the world – men and women in public life, in the world of music and art.

“Much of my education in the past has come through them. With Mrs. Carter, I have often interviewed a visitor, then discussed him and his views just as I would discuss a chapter in history or English.”

And, Judy adds pictures are their own inspiration to learning. Now, for example, she’s the heroine of “Little Nelly [sic] Kelly.” And she’s delving deeply into Irish history and customs.

“It’s surprising,” she laughs, “how much you can learn that way – and how painlessly.”

Check out The Judy Room’s Filmography Pages on Little Nellie Kelly here.

November 6, 1941: Filming continued on Babes On Broadway with scenes shot (some were retakes) on the “Exterior Block Pary,” “Interior Auditorium,” “Interior Penny’s Office,” and “Exterior Cellar” sets. Time called: 1 p.m.; dismissed: 5:20 p.m.

November 6, 1943: Judy took part in a Hollywood Victory Committee show with a holiday theme, recorded to be distributed by the War Department. This recording is not known to exist. It’s not to be confused with the Command Performance recordings Judy took part in, along with some of these same other stars such as Ginny Simms, Dinah Shore, and Frances Langford.

November 6, 1943: In the trade magazine “Motion Picture Herald,” MGM placed this two-page ad. In their “What The Picture Did For Me” feature, Presenting Lily Mars received feedback reviews from the following theatre owners/managers:

A. A. Bolduc of the Majestic Theatre in Conway, New Hampshire simply said, “Entertaining. Heflin Very good.”

W.C. Pullin of the LInden Theatre in Columbus, Ohio, said, “I played this one late, but still did a nice business. Judy Garland is O.K. with my audience.

November 6, 1944: The Clock filming continued with scenes on the “Exterior Street Riverside Drive” and “Interior Milk Truck” sets. The former was on MGM’s Backlot #2, the “New York Streets” section where quite a few of Judy’s films were shot. Judy was due on the set at 10 a.m., arriving at the studio at 9:45 a.m. She didn’t make it to the set until 11:15 at which time she was ready for filming. Time dismissed: 5:55 p.m.

For more about the film of this and Judy’s other films on MGM’s fabled backlot, check out The Judy Room’s “Judy Garland on the MGM Backlot” section. This section provides details (interactive maps, photos, and more) on the locations on the backlot where Judy’s films were made.

That night Judy performed on the “Democratic National Committee” program, broadcast on both CBS and NBC Radio. Judy sang “Gotta Get Out and Vote.” The program was emceed by Humphrey Bogart and featured Claudette Colbert, James Cagney, Irving Berlin, Joseph Cotten, Keenan Wynn, and Groucho Marx.

Listen to Judy’s performance here:

Check out The Judy Room’s Filmography Pages on The Clock here.

November 6, 1945: Filming on Till The Clouds Roll By continued with work on the “Sunny” and “D’Ya Love Me?” numbers shot on the “Interior Circus” set. Time called: 1:30 p.m.; dismissed: 5:45 p.m.

Check out The Judy Room’s Extensive Spotlight on Till The Clouds Roll By here.

November 6, 1946: Judy had been on maternity leave from MGM for a year’s time when on this date she was scheduled to return to the studio for costume fittings for the upcoming production of The Pirate. Judy’s secretary called in sick for her. The tests were rescheduled and Judy did not return to the studio until December 2nd when she completed wardrobe tests and rehearsals for the film.

Photos: Judy and baby Liza Minnelli in a series of photos taken a few months prior.

Check out The Judy Room’s Filmography Pages on The Pirate here.

November 6, 1947: Judy had rehearsals of “A Fella With An Umbrella,” “A Couple of Swells,” and “Mr. Monotony” for Easter Parade. Time called: 2:00 p.m.; dismissed: 4:45 p.m.

Check out The Judy Room’s Spotlight on Easter Parade here.

November 6, 1948: Judy appeared on the cover of “Picturegoer” magazine.

Scan provided by Kim Lundgreen. Thanks, Kim!

November 6, 1949: Judy posed for this make-up test for Summer Stock.

November 6, 1953: Filming on A Star Is Born continued with more scenes shot on the “Interior Danny’s Room” and “Interior Projection Room” sets. Time started: 10 a.m.; finished: 6 p.m.

Check out The Judy Room’s Spotlight on A Star Is Born here.

November 6, 1957: Here’s a nice review of Judy’s wonderful album for Capitol Records, “Alone.”

Check out The Judy Garland Online Discography’s “Alone” pages here.

November 6, 1960: Here’s a nice review of another of Judy’s wonderful albums for Capitol Records, “That’s Entertainment!”

Check out The Judy Garland Online Discography’s “That’s Entertainment!” pages here.

November 6, 1960: Judy is listed as one of the examples of women in Hollywood who attempt suicide (whether successful or not). The article was prompted by Bridget Bardot’s recent attempt.

November 6, 1961: Judy was caught up in a battle between hair stylists! Two printings of the same article.

November 6, 1964: The first of two days of rehearsals for Judy and daughter Liza Minnelli at the EMI Studios in London, England. Judy and Liza were rehearsing for their upcoming concert at the London Palladium.

Exactly one year later, the videotape filmed by ITV British Television of the second concert on November 15th, was broadcast in Sydney, Australia (see the ad above).

November 6, 1965: Judy sang a few songs during a party for Princess Margaret and her husband Lord Snowden, at the Bistro in Beverly Hills, California. According to columnist Earl Wilson, she sang “what the Princess wanted me to sing.” “I Left My Heart In San Francisco,” “Chicago,” and “The Man That Got Away.” No recording of this appearance was made.

Photos: Judy and Mark Herron arriving at the Bistro for the event; newspaper articles chronicling the event. Judy looks just as glamorous as the Princess!

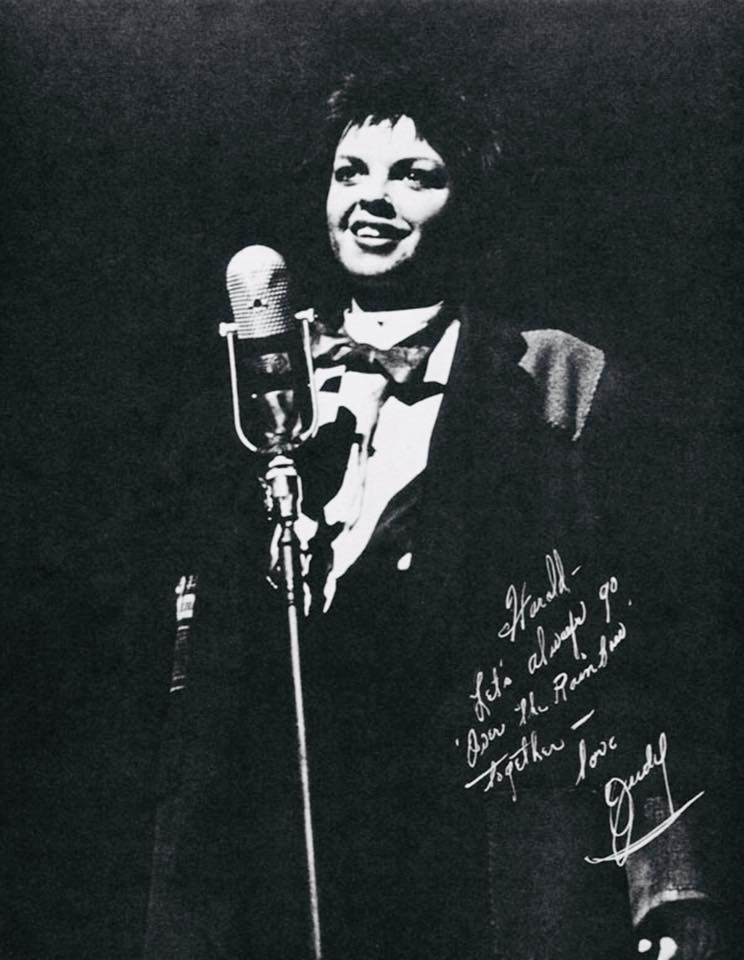

November 6, 1968: Judy had a business meeting with Jay Blackton, the musical director for the Harold Arlen tribute that Judy participated in on November 17th. The meeting took place in John Meyer’s apartment with orchestrator Jim Tyler on hand. The meeting took two hours and set what would be needed for the musical arrangements. Later that evening Judy and Meyer dined at Orsini’s in Manhattan to celebrate the $2,000 worth of free arrangements they’d be getting from the Arlen tribute show.

Photo: Scan of a photo that Judy signed for Harold Arlen.

Check out The Judy Room’s “Judy Garland – The Concert Years” section here.

November 6, 1998: The Wizard of Oz had its first nationwide theatrical re-release in decades, the most recent being the 1972 children’s matinee re-release. The film had recently been restored and the audio converted to stereo utilizing the surviving stereo tracks and the rest being enhanced for stereo. It was quite a wonderful experience to see the restored version on the big screen.

THE MARVELOUS MOVIES OF OZ

Judy Garland and friends were far from the first to follow the yellow brick road

By Jim Mueller

Special to the Tribune

November 6, 1998

Forget your Y2K worries for the nonce and consider one of life’s truly momentous events.

“The Wizard of Oz” returns to movie theaters Friday in yet another repackaging of the 1939 MGM film classic; this time it’s re-mastered in glorious digital sound. We’ll be seeing Miss Gulch again, that crusty sourpuss for the ages, she of the demented cackle and caustic sneer. (Hey, is that really her face, or is Craftsman missing a load of rusty hatchets? Ha! Ha!)

Aye, the Wicked Witch is back, and with her comes all the catty gossip about rogue Munchkins ogling Judy Garland and shooting dice under the sets. We’ll learn once again of Buddy Ebsen’s abbreviated turn as the Tin Man, and the way W.C. Fields had the Wizard role in his vest pocket, then backed away to make “You Can’t Cheat an Honest Man” instead.

Margaret Hamilton toasted her face like a Girl Scout s’more in the fireball stunt; everybody knows that, and Bert Lahr’s Cowardly Lion costume weighed in at an ungainly 70 pounds. However, please rest easy this morning in the knowledge that there’s absolutely no truth to the rumor that one of the Munchkins hanged himself and is clearly visible dangling at the back of the scene where Dorothy meets the Tin Man.

Bad information; never happened.

But did you know Oliver Hardy – of Laurel and Hardy – was in “The Wizard of Oz”?

Yes, it was Ollie himself who played the Tin Man in Chadwick Pictures’ 1925 movie of the same name, and therein lies an interesting tale. It seems the 1939 movie you know as “The Wizard of Oz” is a remake, following versions released in 1910 and 1925. In fact, the MGM Oz holds down 15th place in a series of Oz movies dating back to something called “Fairylogue and Radio Plays,” an early multimedia stage and film show written and produced by Oz creator L. Frank Baum in 1908.

Baum, as most true Oz fans know, was 44 and living in Chicago in 1900 when he and illustrator William Wallace Denslow collaborated on “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” – the first of 14 Oz books he’d write before passing over the rainbow himself in 1919. A theatrical sort who suffered from a weak heart, Baum managed legitimate theaters and opera companies as a young man between stretches as a newspaper reporter.

Peter Schulenburg, author and illustrator of the recent Oz titles “The Tin Castle of Oz” and “The Corn Mansion of Oz” (Tails of the Cowardly Lion Press) knows Oz history well, and he suspects Baum scribbled most of his little yarns with an eye toward the Broadway stage and the fledgling film industry.

“I’ve seen stills from `Fairylogue and Radio Plays’ and have read the script,” says Schulenburg. “Baum would dress up as the narrator. He looked sort of like Hal Holbrook as Mark Twain, if you remember that show. He’d begin his story and stop for a dance sequence or run a piece of film before continuing. I don’t think there’s any doubt the man was a born showman.”

John Fricke, author of “The Wizard of Oz: The Official 50th Anniversary Pictorial History” (Warner Books), agrees. “Oh, yes, Baum started out on stage as a bit of a golden boy in his 20s when he wrote `The Maid of Arran,’ a five-act Irish melodrama that had a long run in New York,” he says. “After his first success, I understand there were reversals in his family fortunes, and he settled into a 20-year period of vamping, working at traveling-salesman jobs and writing nonsense verse at night for his children, some of which included the Oz characters.”

In 1891, Baum moved his family to Chicago and owned homes at what are now 2233 N. Campbell and 2149 W. Flournoy. The home recognized by most aficionados as the Wizard of Oz House, where he lived while writing some of the books, stood at 1667 N. Humboldt Blvd. It was torn down sometime in the late 1950s or early 1960s, before Oz fans could hang a proper plaque.

The success of Baum’s original Oz book — “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” — and its early 1900s Broadway stage adaptation left him flush enough to spend winters in California, where he would settle permanently in 1910. Marginally successful attempts by the Selig Polyscope Co. to recycle chunks of `Fairylogue and Radio Plays’ into 8- to 10-minute one-reelers were enough to encourage Baum the show-business entrepreneur. Capitalizing on his run of good fortune, he formed the Oz Film Manufacturing Co. in 1914; a multiple film package of his work from this period is available on video through American Home Entertainment with titles including “The Patchwork Girl of Oz,” “His Majesty, the Scarecrow of Oz” and “The Magic Cloak of Oz.” In these early silents, viewers were introduced to Oz’s major characters beyond Dorothy, Scarecrow, Tin Man and the Cowardly Lion.

What’s this? Other residents of Oz?

Though most of us incorrectly assume the story of Oz began with a Kansas tornado and ended with a melting witch with green acne, Baum aficionados know better. They are well acquainted with Ozma, Jack Pumpkinhead, Mombi, the Patchwork Girl, the Hungry Tiger and many others.

In fact, Oz has been revisited regularly through the imaginations of several dozen writers, with each trip producing a new member or two for this rather fluid stock company. The first after Baum’s death was Ruth Plumly Thompson, who picked up the Oz series and wrote 19 additional adventures.

To get a take on Oz you haven’t seen a million times, check out the 1925 silent version of “The Wizard of Oz,” available from Video Images. In this movie, Dorothy is introduced as a long-lost Ozian princess who was left on Uncle Henry and Aunt Em’s doorstep as a foundling. The bad guys back home — Prime Minister Kruel and Lady Vishuss — send their minions to Kansas to snatch Dorothy before she can read a secret letter spilling the beans on her royal lineage. So you have five swarthy thugs dressed in what look like badly soiled Zorro suits arriving at Uncle Henry’s farm aboard a biplane. (“I just flew in from Oz, and boy are my arms tired!”) There’s a tussle, the tornado kicks up, everyone lands in Oz and it’s on with the show.

Except it’s really the Scarecrow’s story this time out, as Larry Semon, an interesting yet forgotten film comic of the 1920s, is writer and director here in addition to playing the old bag of straw. Semon saves the funniest bits for his character, including a crude live-action/animation scene where he’s chased by a swarm of bees. A younger, somewhat slimmer Oliver Hardy turns up as Dorothy’s clumsy love interest, lumbering about the screen in farmhand and Tin Man outfits. (One warning about this version: It includes a terribly offensive African-American stereotype in the Snowball/Rastus character, who eats watermelon and flops around like a goof.)

“L. Frank Baum was first and foremost an entertainer,” says Fricke. “He wrote for the printed page, stage and film, and all of his stories were created for the single purpose of making kids and adults laugh out loud. He used to say, `To please a child brings its own reward.’ “

Yes, but was Baum writing Oz books with a serious eye toward producing screen and stage adaptations?

“I don’t think there’s any doubt,” Fricke says. “He seesawed between stage and the printed page. His second play, `The Tik-Tok Man of Oz,’ toured the West Coast, playing Los Angeles and San Francisco around 1910, and the plot and characters from this production were later developed as one of Baum’s first silent film efforts, `His Majesty, The Scarecrow of Oz.’ He also wrote `The Woggle Bug’ with the idea of adapting it to the stage. The story includes an army of girls that was quite obviously intended for a production number at some later date.”

Even though the 1925 film was a major flop, according to Fricke, it would appear Baum was correct in his assessment of his creation’s screen and stage potential. Besides the 1939 MGM jewel’s firm entrenchment in pop culture, consider Oz’s more recent Broadway and film incarnation as “The Wiz” for pure commercial punch. Perhaps the secret lies in the timelessness of Oz? The Emerald City has no rusty Buicks, no references pinning it to a specific period. It’s pure fantasy, which all goes back to the author.

“Baum himself had such great charisma, such a commanding stage presence. Before she died I talked to Romola Remus Dunlap, the original screen Dorothy from `Fairylogue and Radio Plays.’ She described a gentle, kind man who was great with kids, who took time to entertain the children in the cast with his stories. The man was a dreamer, but thank God he was — and it all started in Chicago.”